Tate Gallery of Modern Art International Design Competition Ando

Once the Tate had settled on the inactive Bankside Power Station equally the home of what was then to be the Tate Gallery of Modern Art in 1994, a competition was launched to find the architects to turn this hulking edifice into a museum. From 150 submissions, a shortlist of xiii architects was invited to set schemes, and this was further whittled downward to vi finalists who would submit detailed proposals.

In 1994, Herzog & de Meuron were not the "starchitects" they are today, and had the Tate's console been less willing to put its faith in a relatively immature practice, or been more than inclined to favour British architects, for instance, we might have had a very dissimilar museum.

It was a tricky brief, every bit Michael Craig-Martin, then a Tate trustee and on the competition console, recalls. "Bankside Power Station wasn't really a building, it was a shoebox. Information technology was four exterior walls with a big car in it, and when you took out the big machine all you lot had was a giant empty box," he says. "I think what Herzog and de Meuron did was the most brilliant motion—having the Turbine Hall equally the middle of the museum rather than the periphery, and making the entrance on the lower level, which fabricated the whole matter grander. Information technology is extraordinarily clever and built for peanuts, really, given its size and importance."

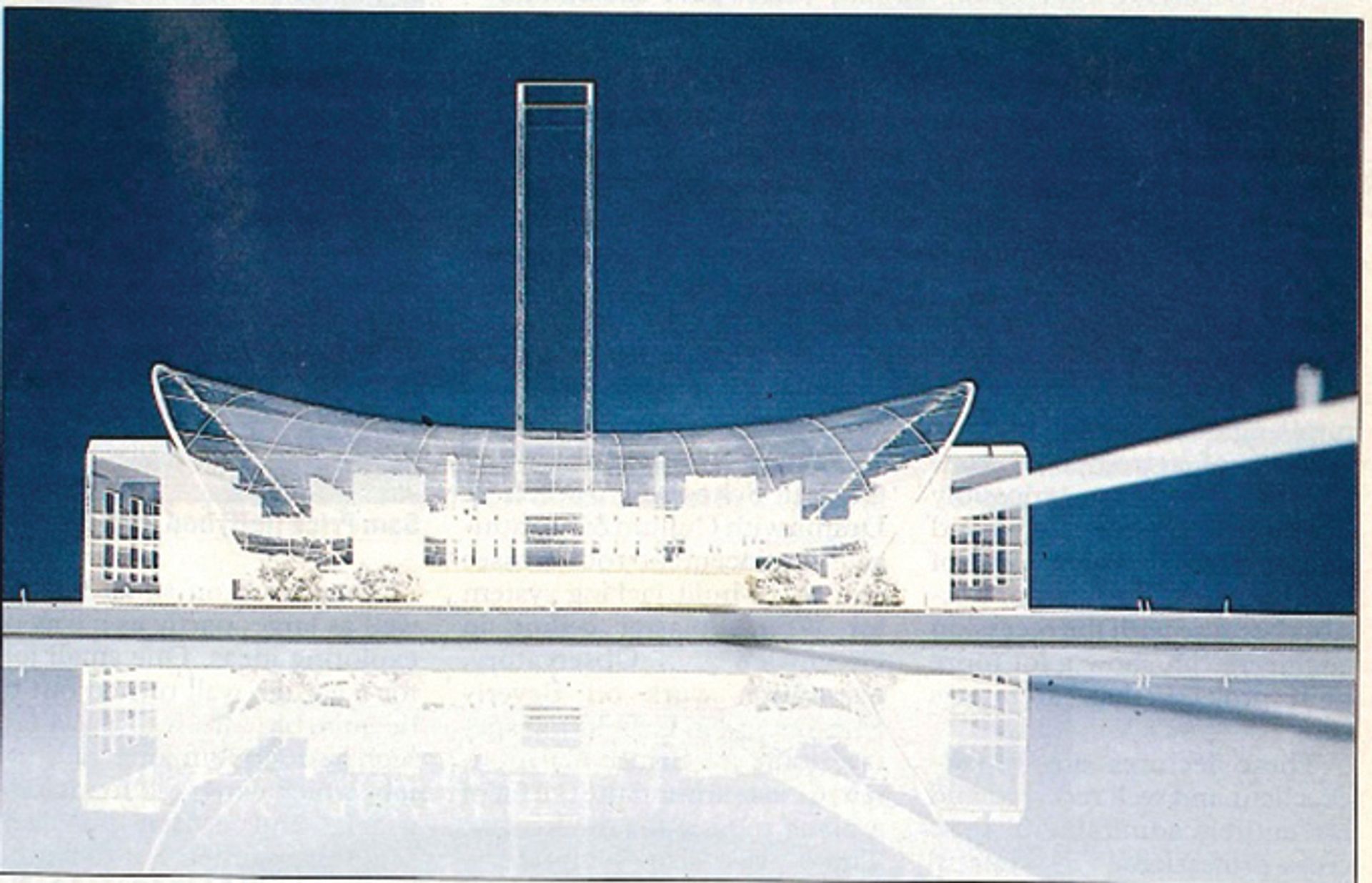

Amid those to be jettisoned at shortlist level were a host of British practices, including Alsop & Störmer, Future Systems, Michael Hopkins & Partners, and Nicholas Grimshaw & Partners. Future Systems's pattern was clearly formally consistent with their media center at Lord's Cricket Footing, with a spacey glass awning—they would also have removed the Turbine Hall, now Tate Modern's most famous infinite.

The list of finalists must surely exist among the most prestigious groups e'er gathered for a competition: Rafael Moneo, David Chipperfield, Herzog & de Meuron, Tadao Ando Builder & Assembly, Renzo Pianoforte Building Workshop and Rem Koolhaas/OMA. Whoever won, London was promised world-class international architecture.

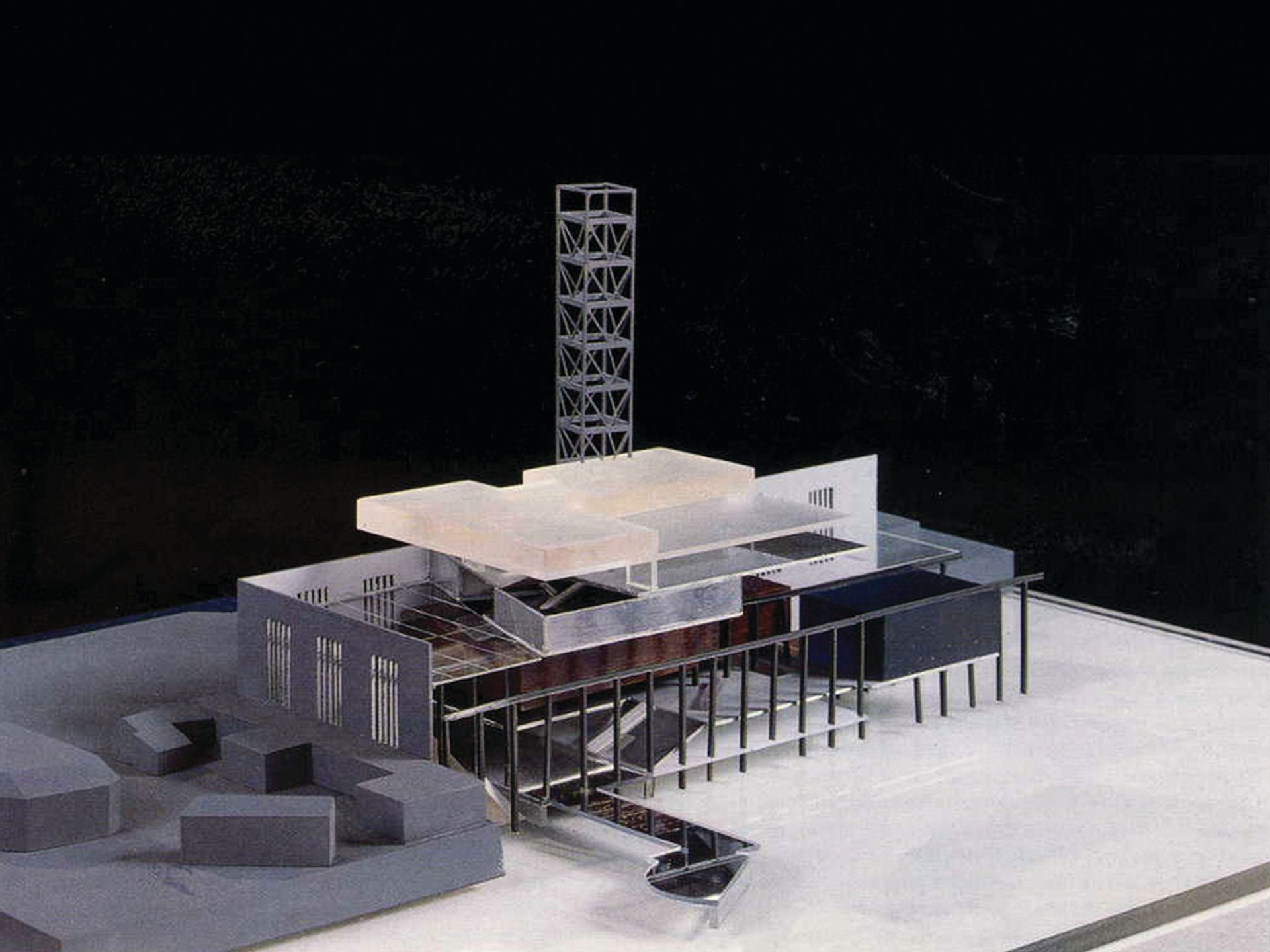

The proposals varied greatly, just much interest focused on the stand-out chemical element of Bankside: its chimney. Koolhaas would have stripped information technology of its bricks and turned it into a steel skeleton; Chipperfield did the unthinkable and proposed removing the chimney altogether.

All the architects proposed various additions to the stark geometry of Giles Gilbert Scott's ability station. But there was a clear winner during the presentations, every bit Craig-Martin remembers. "It was an amazing state of affairs considering some of the greatest architects in the world came in and I was part of the client," he says. "And what was very interesting is that almost great architects hated the thought that they had to build something inside a shell designed past somebody else. Virtually architects desire the profile of the building, and the limitation was that they had to put it inside this existing edifice."

A common trait emerged: "When they made their presentations, each had to make a model the same size. Then each architect came in with the model and almost invariably would grab the chimney and elevator the shell off. Inside would be the edifice that they actually would accept liked to have built, had information technology not been for the vanquish.

"The only architects who truly turned the building into a building itself were Herzog & de Meuron. Everybody else built something in it; they proposed turning it into a building."

This response was partly "generational", Craig-Martin suggests. "[Herzog & de Meuron] were non put off by the sense that they were transforming an existing building; they'd done a lot of buildings already that had involved doing that, and that is a much more gimmicky practice than a traditional Modernist practise. It only seemed right for that project."

The Tate announced Herzog & de Meuron every bit the architects in January 1995. Twenty-2 years afterward, that relationship continues to thrive.

• The photo in a higher place features the following people, numbered from the left: 1) Hiromitsu Kuwata, architect, Tadao Ando'south team, 2) Masataka Yano, architect, Tadao Ando's squad, v) Julian Harrap, architect, specialist in the restoration of historic buildings, 6) Amanda Levete, then at Future Systems, 7) Jan Kaplický, Future Systems, eight) Ricky Burdett, builder on the judging panel, ix) Nicholas Grimshaw, shortlisted builder , 10) Shunji Ishida (in forepart), builder and fellow member of Renzo Piano'due south team, 13) Rick Mather, shortlisted builder, fourteen) Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate, 15) John Pringle, architect, then at Michael Hopkins and partners, 16) Michael Craig-Martin, artist and Tate trustee, on judging console, 17) Mark Whitby, structural engineer , nineteen) Renzo Piano, shortlisted architect, 20) Jacques Herzog, winning architect, 21) Volition Alsop, shortlisted architect, 22) Rem Koolhaas, shortlisted architect, 24) Claudio Silvestrin, shortlisted builder with Rolfe Judd, 26) Rolfe Judd, shortlisted architect, 27) David Chipperfield, shortlisted architect. Members of the architectural teams of Rafael Moneo and Arata Isozaki were also present simply cannot be identified

Source: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2016/06/15/the-ones-that-got-away-tates-rejected-designs

0 Response to "Tate Gallery of Modern Art International Design Competition Ando"

Post a Comment